Despite growing public awareness and concern over how animals are treated in our food industry, vegans are still not well-received by the general public. Discover what research reveals about why people hate vegans. The reasons may not be what you expect!

This article and video review the growing scientific field of study into why people tend to view vegans so negatively. Interestingly, the underlying drivers of anti-vegan attitudes may point more to promising commonalities than irreconcilable differences. As we look through the scientific literature, we explore such areas as:

- The widespread existence of anti-vegan bias

- The threat vegans pose to our identity, sense of self, and way of life

- That animosity towards vegans can actually be a sign that we share the same values and beliefs

- How vegans think they’re better than everyone (and how we may actually agree with them)

- How we tend to assume we’re being judged by one another (and defensively judge each other)

- That the more we agree with each other, the more we can resent one another

- How omnivores can empathize with the experience of vegans facing social stigma

- And, most importantly, the lessons we can all learn from this

Read more below (or watch the video above) for a deeper dive into the surprising science of why people hate vegans.

Despite growing public awareness and genuine concern over how animals are treated in our food industry and the industry’s role in the climate crisis, vegans are still not well-received by the general public. In fact, vegans are often viewed so negatively that there’s a growing field of scientific study into why. And the reasons…may not be what you expect. tweet this

In this article and video, we’ll break down the findings of these studies and explore the surprising thread I found throughout the research: the magnitude of passion and degree of polarization between vegans and non-vegans is fueled more by what we have in common than by our differences.

In fact, if I can be so bold as to offer my own personal thesis: if you bristle at the mention of veganism and vegans, you…may just be a good person.

A Note on Terminology & Limitations

Before we dive in, I want to clarify some terminology and limitations.

Terminology

- Veg*ns:

The studies we’ll be covering are mixed in whether they analyzed just vegetarians, just vegans, vegetarians and vegans as one group (denoted by the term veg*ns), or as separate groups. I’ve aimed to accurately relay the distinctions for each study, though this can be challenging when referring to the findings of multiple studies which varied in their grouping. - Omnivore/omnivorous:

There’s no widely accepted term for people who consume animal products, as it’s viewed as the “default” way of eating (see Dr. Melanie Joy’s work for an in-depth exploration+Dr. Melanie Joy proposed the terms “carnism” and “carnist,” which have been adopted and explored by many researchers. She explains: “We sometimes think of those who eat animals as carnivores. But carnivores are, by definition, animals that are dependent on meat to survive. Those who consume animals are also not merely omnivores. An omnivore is an animal—human or nonhuman—that has the physiological ability to ingest both plants and meat. Both “carnivore,” “omnivore” are terms that describe one’s biological constitution, not one’s philosophical choice. In much of the world today people eat animals not because they need to, but because they choose to, and choices always stem from beliefs. […] We eat animals without thinking about what we are doing and why because the belief system that underlies this behavior is invisible. This invisible belief system is what I call “carnism.”” (Melanie Joy. Why We Love Dogs, Eat Pigs, and Wear Cows) ).1 The majority of studies covered in this article and video use the term “omnivore,” though one researcher2 points out the problematic ambiguity of the term as it can be interpreted as both biological (omnivore, herbivore, carnivore) and behavioral (omnivore, vegetarian, vegan). For consistency and familiarity, I’ll retain the use of “omnivore” and “omnivorous.” - My use of “we”:

Throughout this article and video, I use the term “we” liberally. I use it when referring to omnivores, despite being vegan myself. This is a conscious choice because the psychosocial dynamics explored throughout these studies are human. None are isolated to vegans, vegetarians, or omnivores. It’s actually the commonality of our psychology and sociological behavior that underpins the more visible polarization.

Limitations

I read over eighty studies for this article and video, all of which speak to very complex and rich aspects of our humanity. There’s no way to account for the individuality of every person, nor the complexity of every study in a single article or video.

While I’ve done my best to present the thematic threads throughout the research, I’ve had to simplify and generalize. I highly recommend reading through the studies themselves for a more thorough understanding of the science. And I just want to acknowledge the generalization of human motivations and behaviors that results from any attempt to quantify and summarize what makes us tick.

Yes, People Do Dislike Vegans (Establishing Anti-Vegan Bias)

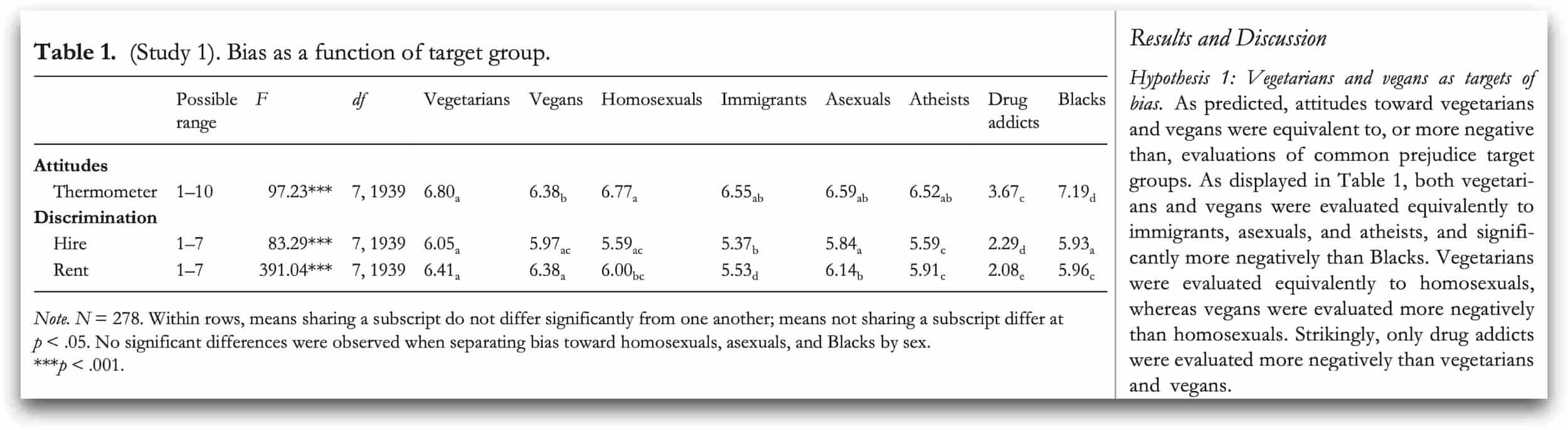

Source: MacInnis, Cara C., and Gordon Hodson. “It Ain’t Easy Eating Greens: Evidence of Bias toward Vegetarians and Vegans from Both Source and Target.”

Before we explore why people hate vegans, let’s take a moment to establish the presence of anti-vegan bias. When researchers asked omnivores to evaluate vegans along with several “common prejudice target groups,”3 (lesbians, gay men, immigrants, asexual women, asexual men, atheists, drug addicts, Black women, and Black men) they found that:

“Strikingly, only drug addicts were evaluated more negatively than vegetarians and vegans.”4

The study’s authors, Cara C. MacInnis and Gordon Hodson, noted a unique aspect of anti-vegan bias:

“Unlike other forms of bias (e.g., racism, sexism), negativity toward vegetarians and vegans is not widely considered a societal problem; rather, negativity toward vegetarians and vegans is commonplace and largely accepted.”5

Given that most people care about animals and don’t want to cause them harm, why is there so much animosity toward people who try to cause the least harm possible?

In fact, research has revealed widespread anti-vegan bias not only in the media but even within academic research itself.

A study of UK media found that 73.4% of references to vegans were negative,6 and a review of social science literature discovered that researchers used terms that “denigrated [veganism] and made…[it]…seem ‘difficult’ and abnormal.”7

There are also degrees of bias within the veg*n spectrum. Vegans were consistently rated worse than vegetarians,8 and their reason for being vegan also impacted the ratings: the very worst-received were vegans motivated by ethical concerns for animals, followed by environmental, and, finally, health-motivated.9

Given that most people care about animals and don’t want to cause them harm,10 why is there so much animosity toward people who try to cause the least harm possible? This is one of the many questions social scientists have set out to answer.

Vegans Threaten Our Identity

The first set of research we’ll look at frames anti-vegan bias as a defense mechanism against threats to our moral self-image, group identity, and way of life. These are deep-seated aspects of our humanity and can understandably result in very strong reactions when threatened.

Later, we’ll explore research that uses a social framework for vegan resentment, focusing on the impressions of vegans as judgy, self-righteous, and having an insufferable sense of superiority. While these may sound like superficial reasons, they all connect to the more profound components of our nature that we’ll discuss first.

Vegans Threaten Our Moral Sense of Self & Trigger the Meat Paradox

Some social psychologists argue that negativity toward vegans has less to do with vegans themselves than what they represent11 and bring to mind.12 We usually don’t think about eating animal products as a conscious choice. It’s simply what everyone else does.13

Interestingly, the source of this particular animosity toward vegans is not disagreement, but actually a shared value and belief: that it’s wrong to harm animals.

tweet this— Emily Moran Barwick

This is one of the reasons we don’t have a standard word for people who consume animals: it’s viewed as the default way of eating, so we only need words for those who deviate.

However, the mere presence of a vegan immediately shifts meat-eating from the comfort of an unexamined social norm to the disquieting reality of a choice.

This triggers what researchers call the “meat paradox:”14 simultaneously believing it’s wrong to harm animals, yet continuing to eat them.

“At the heart of the meat paradox,” explains social psychologist Hank Rothgerber, “is the experience of cognitive dissonance,”15 which is the psychological tension caused by holding conflicting beliefs at the same time, or taking actions that directly contradict one’s values. Examples relayed by Rothgerber include:

- “I eat meat; I don’t like to hurt animals” (classic dissonance theory focusing on inconsistency),

- “I eat meat; eating meat harms animals” (the new look dissonance emphasizing aversive consequences), and

- “I eat meat; compassionate people don’t hurt animals” (self-consistency/self-affirmation approaches emphasizing threats to self-integrity).16

In his research, Rothgerber identified at least fifteen defenses omnivores use to both “prevent and reduce the moral guilt associated with eating meat.”17 One of these methods is to attack the person who triggered the discomfort.

Most people who eat meat and animal products don’t want to hurt animals and experience discomfort about this conflict.

Feeling that conflict is not something to be criticized—it’s a sign of your humanity.

tweet this— Emily Moran Barwick

It’s human nature to lash out at anyone we perceive as a threat. And vegans threaten something we hold very dear: our moral sense of self.18 We like to think of ourselves as good and decent people.19 We also believe that good and decent people don’t harm animals.

We’re generally able to maintain these conflicting beliefs without much discomfort because the majority of society does as well. Eating animals is accepted as normal, often considered necessary and natural20—even completely unavoidable.21 But the existence of vegans alone challenges these comforting defenses.

This is what I meant when I said that “if you bristle at the mention of veganism or even outright hate vegans, you…may just be a good person.” While that’s certainly an oversimplified statement designed for a catchy video intro, there is truth to it.

Most people who eat meat and animal products don’t want to hurt animals and experience discomfort about this conflict. If that’s you, you’re not alone.

We’ve all been taught not to listen to our emotions toward the animals we eat. Feeling that conflict is not something to be criticized—it’s a sign of your humanity. It’s a sign of empathy and compassion struggling against behavior, conditioning, identity, and an understandable desire for belonging.

Vegans Threaten Our Way of Life & Challenge Social Norms

Vegans don’t just pose a threat to our individual identities as moral people—they also pose what researchers call a “symbolic threat”23+As outlined by intergroup threat theory (W. S. Stephan & Stephan, 2000) symbolic threats are intangible threats to an ingroup’s beliefs, values, attitudes, or moral standards. These threats originate from the perception that an outgroup’s beliefs, values, attitudes, or moral standards are in conflict with those of one’s own group. As such, symbolically threatening groups can be perceived as undermining the cherished values of the ingroup.” (MacInnis, Cara C., and Gordon Hodson. “It Ain’t Easy Eating Greens“) to group identities, cherished traditions, cultural values, and social norms.24 So much of our social customs are built around food. This invariably leads to friction when someone is seen as challenging those customs.

Research shows the more firmly people associate meat-eating with their identity, the more likely they are to perceive vegans as a threat to their way of life, and thus the more they will engage in a variety of defenses, including stigmatizing and attacking vegans.25

Within the framework of intergroup threat theory,+“In the context of intergroup threat theory, an intergroup threat is experienced when members of one group perceive that another group is in a position to cause them harm. We refer to a concern about physical harm or a loss of resources as realistic threat, and to a concern about the integrity or validity of the ingroup’s meaning system as symbolic threat. The primary reason intergroup threats are important is because their effects on intergroup relations are largely destructive.” (Stephan, Walter G., Oscar Ybarra, and Kimberly Rios Morrison. “Intergroup Threat Theory.”) the more a minority group (or “outgroup”) deviates from what’s seen as “normal” to the majority group (or “ingroup”), the more negatively they are viewed.26 This is one way of explaining why vegans were consistently rated worse than vegetarians across multiple studies.27

Social psychologists Cara MacInnis and Gordon Hodson approached their research into vegan bias through an intergroup relations+“Intergroup relations refers to the way in which people who belong to social groups or categories perceive, think about, feel about, and act towards and interact with people in other groups.” (Hogg, Michael A. “Intergroup Relations.” In Handbook of Social Psychology) approach, with veg*ns as the “outgroup” and omnivores as the majority “ingroup.” What they found interesting was the unique way in which veg*ns may be viewed as threatening to the ingroup.

Outgroups, they explain, are usually considered threatening because they perform actions and behaviors that the ingroup does not, like immigrants speaking a different language, or religious groups wearing a turban or hijab.28 Veg*ns, they argue, do not fit within this model:

“Instead of engaging in antinormative behavior, vegetarians and vegans fail to engage in normative behavior. Thus, vegetarians and vegans may be viewed as threatening in a unique way, enhancing their potential to be targets of bias given their resistance to cultural norms that sanction eating meat.”29

(emphasis added)

Essentially, they argue that vegans may upset people not so much by what they do, but by what they refuse to do.

The threat vegans pose to the non-vegan majority can lead to a polarized “us” versus “them” mentality. Yet research shows that omnivores don’t have exclusively negative attitudes about vegans.

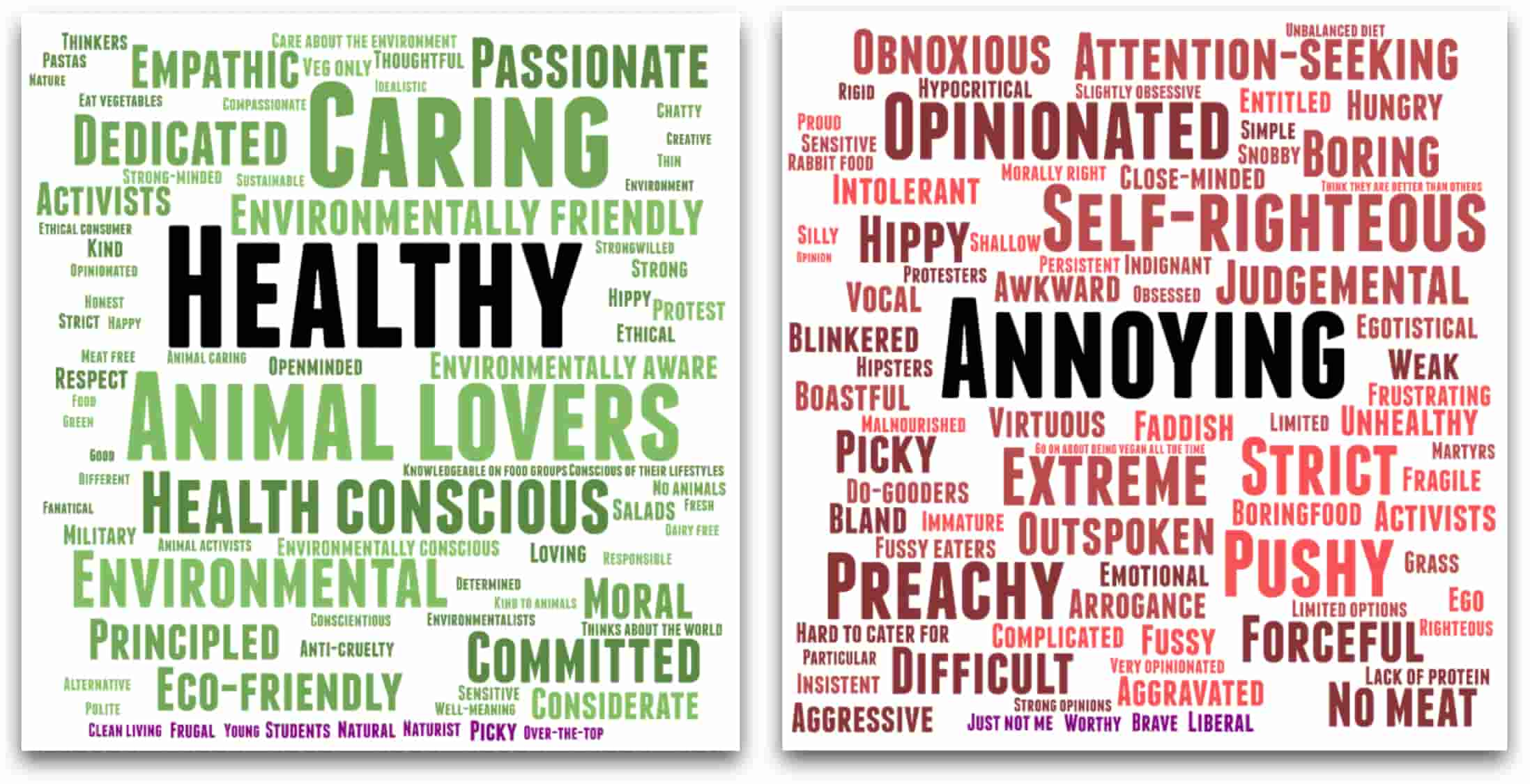

Source: Ben De Groeve et al. “Moral Rebels and Dietary Deviants: How Moral Minority Stereotypes Predict the Social Attractiveness of Veg*ns.”

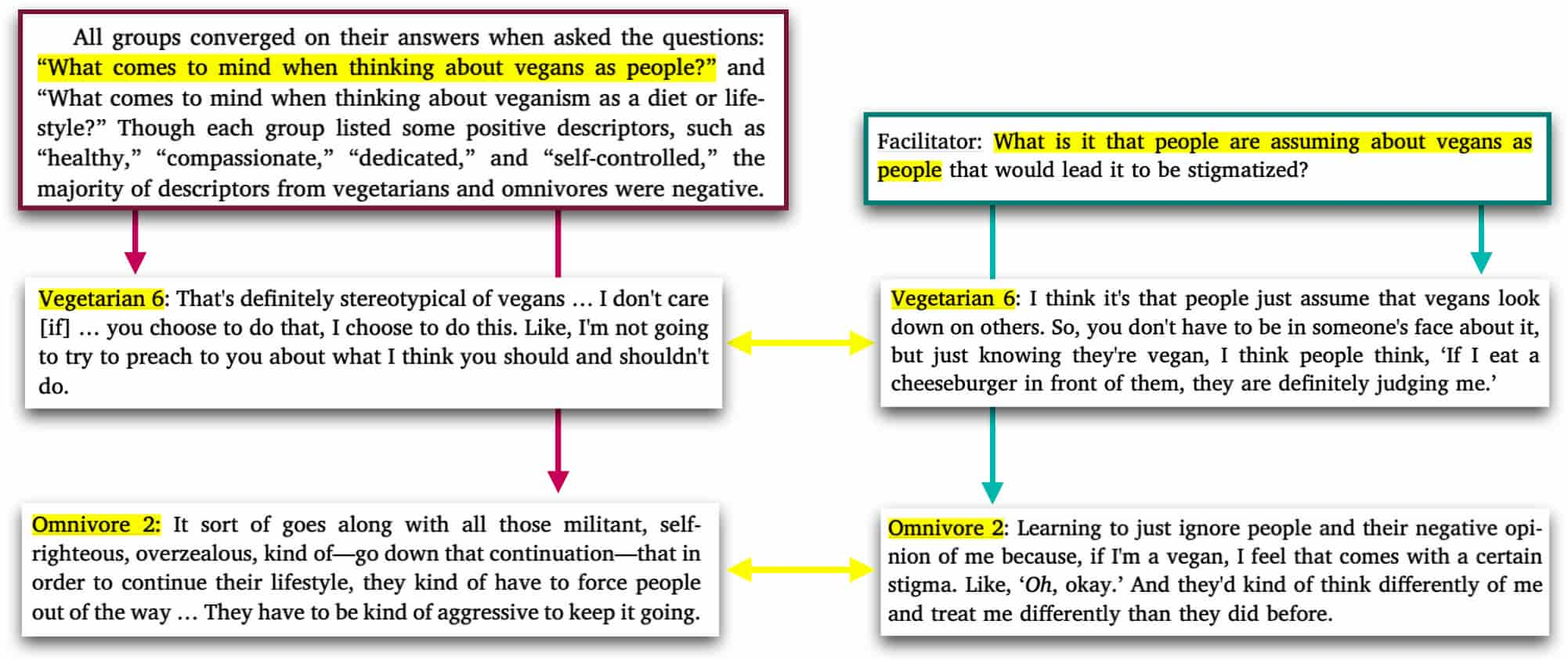

A study led by researcher Ben De Groeve in which omnivores were asked to free-associate words with vegans, vegetarians, flexitarians, and other omnivores,30 found that while omnivores do hold negative views of vegans, they also tend to regard them as caring, committed, empathic, and dedicated.31

Still, these positive traits were often overshadowed by the impressions of vegans being annoying, self-righteous, judgmental, and arrogant.32 Essentially, that vegans think they’re better than everyone.

(We Think) Vegans Think They’re Better than Everyone (and Some Do…and So Do We!)

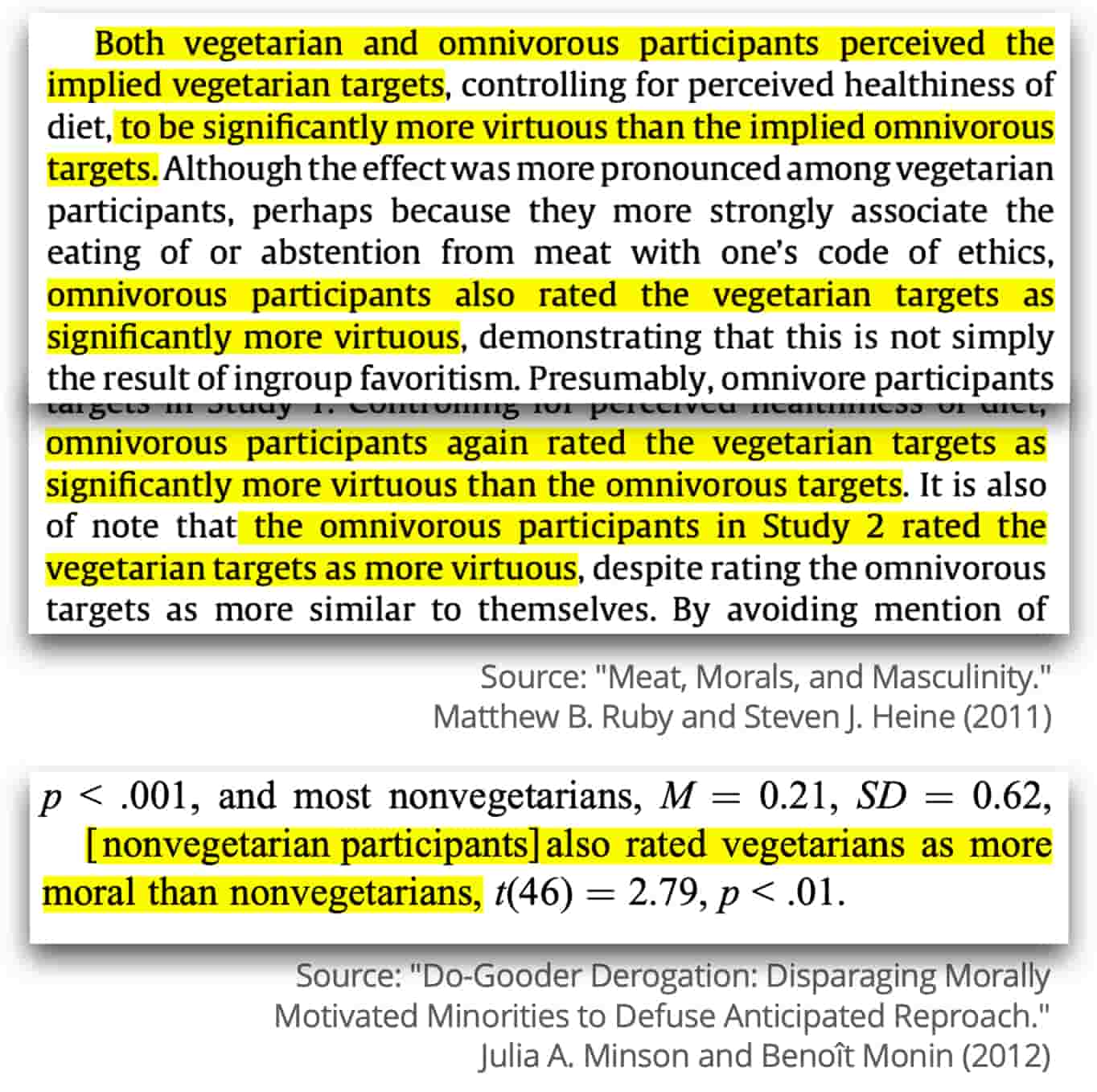

The most prominent negative impression of vegans across studies was that they think they’re better than everyone else.33 Research indicates there is truth behind this stereotype. Studies found that vegans tend to look down on vegetarians,34 ethically-motivated veg*ns look down on health-motivated veg*ns,35 and vegetarians rate other vegetarians as more virtuous than omnivores.36

At the same time, omnivores also rated vegetarians as more virtuous and moral than non-vegetarians,37 viewing veg*ns overall as highly moral.38

Research shows that the more we share the same morals with someone, the more we resent them when they’re willing to act on those morals in a way we are not.39 It comes across to us as an indictment not only of our actions—or lack thereof—but of us as a person. And that is the definition of being looked down upon.

This is all the more distressing if we are personally conflicted about the behavior we feel is being criticized, and what it says about us. We are likely to become preemptively defensive and assume the person thinks they’re better than us, whether they do or not.40

Research into social cognition+Social cognition is a topic within psychology focusing on how people perceive, think about, interpret, categorize, and judge the social behaviors of others and themselves. (paraphrased from the APA Dictionary of Psychology) has found that the way we judge groups of individuals, as well as how we conceive of our own self-image, can be divided into at least three+This three-dimensional model is relatively new, though distinctions of morality and sociability (albeit not always with identical terminology) have been made for decades. (See the opening discussion in Landy, Piazza, and Goodwin 2016). In his doctoral thesis published in 2015, Justin Frederick Landy, Ph.D. challenged the existing two-dimensional model, within which morality and sociability were combined within a single dimension, usually referred to as “warmth.” Landy further investigated the three-dimensional model in a 2016 study. distinct dimensions:41

- morality (being “principled, honest, fair, dedicated, responsible, and sincere”),42

- sociability (being “warm, friendly, easy-going, extroverted, [and] playful”),43 and

- competence (being “capable, intelligent, effective, skillful, [and] talented.”)44

When it comes to our judgment of others, morality is the most important dimension45 and is the only one of the three “considered [to be] universally positive.”46 Competence and sociability, on the other hand, can be positive or negative depending on morality.47

For example, in an individual regarded as immoral—like a serial killer—high competence and sociability suddenly become menacing traits as they enhance the immoral individual’s ability to successfully carry out immoral acts. The opposite is true for moral actors, for whom high competence and sociability are favorably viewed as enhancing their ability to carry out moral acts.

This is what makes the negative impressions of vegans so interesting. Studies show that omnivores perceive veg*ns as moral, even rating them as more moral than non-veg*ns.48 They also rated veg*ns as competent.49 Yet, omnivores still had an overall negative impression of vegans,50 even to the extent of finding their morally-motivated actions outright menacing.51 If morality is, in fact, universally positive and the most important factor in our evaluation of others, how is this possible?

This is one of many questions researcher Ben De Groeve has explored in his work52 on the moralistic+De Groeve defines “moralistic” as “having a self-righteous and narrow-minded moral attitude.” (De Groeve et al. “Moral Rebels and Dietary Deviants”) stereotyping of vegans, and within his theoretical framework connecting the meat paradox with what he calls the “vegan paradox”53 (viewing vegans positively as moral and committed, yet negatively as arrogant and overcommitted54) all of which I highly recommend reading.

(We Think) Vegans Are Judging Us (and Some Vegans Are…and So Are We!)

No one likes to feel judged. It instantly raises our defenses and threatens our sense of self. This threat is so powerful that the judgment doesn’t even have to be real for us to react strongly.55

This phenomenon is called “anticipated moral reproach”;56 it’s when we assume someone is judging our morality (or we expect that they would). This can lead to us preemptively attacking and disparaging them in order to protect our own self-image.57

The more we think we’re being judged, the more we resent the source of that presumed judgment. A study led by Julia Minson found that omnivores rated vegetarians more negatively if they were first asked to imagine how vegetarians would judge them.58

The researchers, Julia A. Minson and Benoît Monin, had two groups: the “Threat First condition” and the “Ratings First condition.” As they describe it, “In the Threat First condition, participants first reflected on how they would be seen by vegetarians, before rating vegetarians on a series of traits. In the Ratings First condition, this order was reversed.”

The way they created this “threat” of moral reproach was by “asking participants to complete 4 phrases using a response on a 7-point scale ranging from extremely immoral to extremely moral:

- ”I would say I am _____,”

- ”If they saw what I normally eat, most vegetarians would think I am _____,”

- ”Most nonvegetarians are _____,” and

- ”Most vegetarians think that most non-vegetarians are_____”

These questions were intended as a moral threat by forcing participants to consider the gap between how they saw their own morality and how they expected to be perceived by vegetarians.” (All quoted text is from the study “Do-Gooder Derogation: Disparaging Morally Motivated Minorities to Defuse Anticipated Reproach.”59)

Studies indicate that omnivores tend to overestimate the degree of actual judgment from vegans60 and, at times, create it entirely. Even the mere mention of a theoretical person being vegetarian or vegan was shown to prompt defensive reactions.61

Omnivores anticipate being judged by vegans and vegans anticipate being seen as judgmental by omnivores. The anticipation of judgment on all sides only escalates everyone’s defenses, making meaningful communication challenging.

As we’ve discussed, some researchers propose that this heightened defensiveness has less to do with the actual judgment of vegans than the self-judgment they trigger.62 This is true for all of us. We react most strongly to external judgments when they hit the pain points of our internal uncertainties and insecurities.

At the same time that omnivores anticipate being judged by vegans, vegans anticipate being seen as judgmental by omnivores and take their own defensive measures.63

The anticipation of judgment on all sides only escalates everyone’s defenses, making meaningful communication challenging.

But before you think it’s hopeless, I want to highlight a particular study that will lead us into what we can learn from all of this.

(We Think) People Would Hate Us if We Were Vegan (and Think of Us How We Think of Vegans)

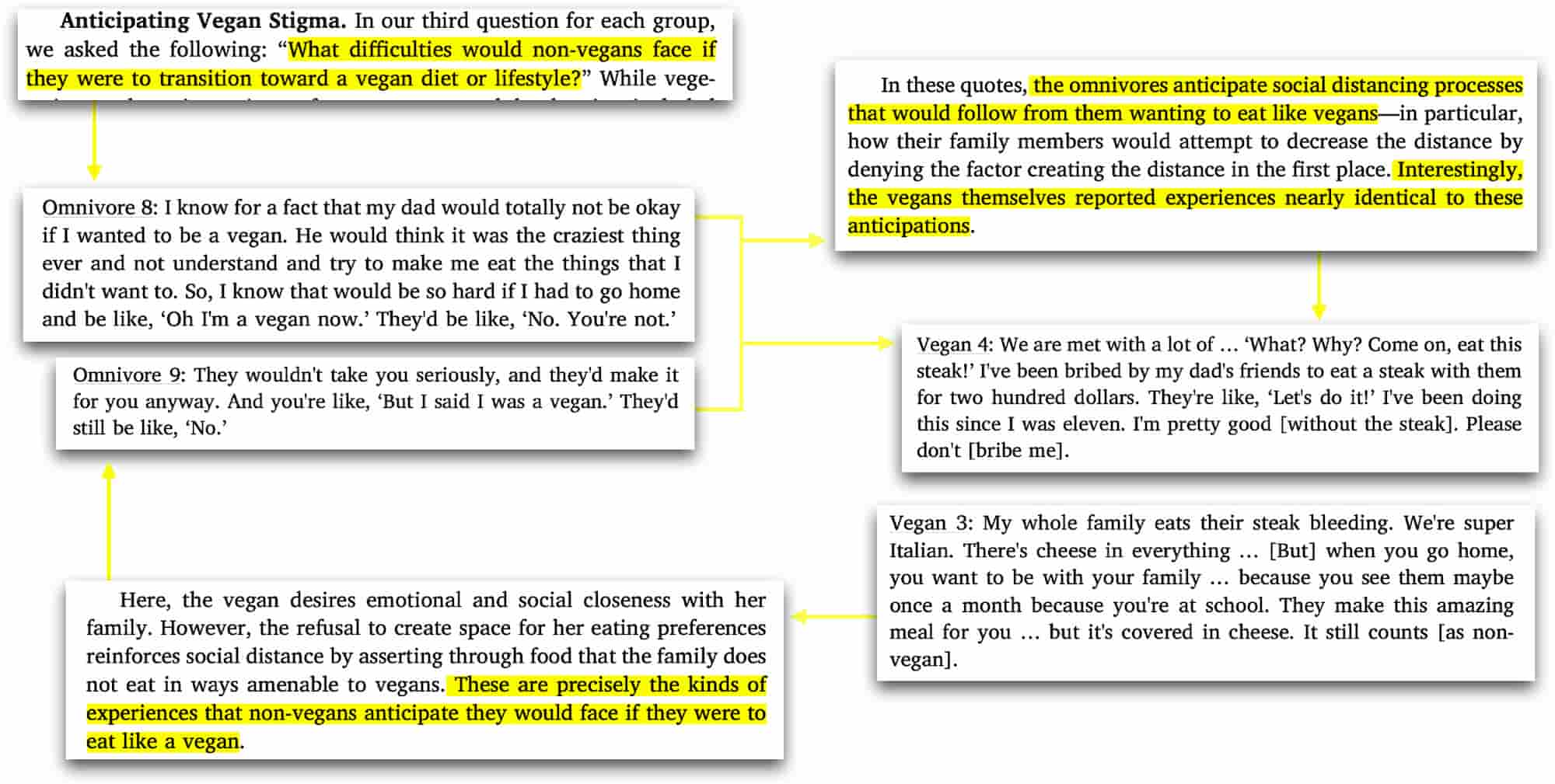

A fascinating study by Kelly Markowski and Susan Roxburgh held separate focus groups of vegan, vegetarian, and omnivorous students to talk about their perceptions of vegans and veganism.64 They found that:

“when imagining what it would be like to be…vegan, non-vegans largely imagined they would be viewed and treated in the same way they view and treat vegans: negatively in a stigmatized fashion.”65

When asked what challenges they’d face if they were to go vegan, the non-vegans imagined scenarios that were nearly identical to real-life painful experiences vegan participants had described, such as rejection and mockery from friends and family.

Source: Kelly L. Markowski and Susan Roxburgh. “‘If I Became a Vegan, My Family and Friends Would Hate Me:’ Anticipating Vegan Stigma as a Barrier to Plant-Based Diets.”

Markowski and Roxburg concluded that the fear of receiving the same treatment as vegans was a strong deterrent to ever going vegan or even associating with vegans—so much so that both omnivores and vegetarians further judged and stigmatized vegans to create more distance from the very kind of judgments they projected.66

While these findings certainly highlight social barriers between non-vegans and vegans, I think there’s something promising in what the study participants shared: evidence that we can see from each other’s perspective.

But…We Can See from Each Other’s Perspectives

With all the bias, judgment, self-righteous stereotyping, and social stigmatization that we’ve covered, it may be hard for vegans and non-vegans to think the other group could see from their perspective. Especially if someone is actively voicing a negative opinion of them. But the students in Markowski and Roxburgh’s study demonstrated that we may not be as polarized as we seem.

When asked what it is that people assume about vegans that makes them seem so unlikeable, the very same vegetarian who earlier cast vegans as preachy said:

“I think it’s that people just assume that vegans look down on others. So, you don’t have to be in someone’s face about it, but just knowing they’re vegan, I think people think, ‘If I eat a cheeseburger in front of them, they are definitely judging me.’”67 (emphasis added)

— Vegetarian study participant who earlier cast vegans as preachy

Similarly, an omnivore who described vegans as “militant, self-righteous, [and] overzealous” expressed that if he went vegan, he’d have to learn to ignore people’s negative opinions of him because “they’d kind of think differently of me and treat me differently than they did before.”68

Source: Kelly L. Markowski and Susan Roxburgh. “‘If I Became a Vegan, My Family and Friends Would Hate Me:’ Anticipating Vegan Stigma as a Barrier to Plant-Based Diets.”

With just a shift in questioning from what they thought about vegans to what they thought people assumed about vegans or would think about them were they vegan, the same students who were critical of vegans were quickly able to empathize with their experience.

What Can We Learn from This?

Whether omnivore, vegetarian, or vegan, most of us want to be seen as good people. We don’t want to harm animals. We don’t like being judged or looked down upon. We fear rejection, isolation, and mockery. We often defensively inflict upon others what we fear experiencing most ourselves.

The more open-minded we as a society can become about transitioning away from eating animals, the more welcome people will feel to make a change.

The less we fear rejection and judgment from one another, the more we can connect on our shared values and with all that makes us human.

tweet this—Emily Moran Barwick

This is what I mean when I say it’s often what we have in common that paradoxically drives our polarization. tweet this

Social psychologist Hank Rothgerber proposes that the more we can understand what’s underlying the strain and tension between non-vegans and vegans, the better we can navigate our interactions.69 He suggests that even seemingly combative quips from omnivores “are not likely motivated by personal cruelty but by personal distress.”70 (emphasis added)

In the final study we covered, when asked what would help them transition towards veganism, omnivores and vegetarians alike emphasized the need for supportive friends and family, and for people, in general, to be more open-minded.71

Essentially, to know they’d be accepted and not have to fear being hated.

The more open-minded we as a society can become about transitioning away from eating animals, the more welcome people will feel to make a change. The less we fear rejection and judgment from one another, the more we can connect on our shared values and with all that makes us human.

In Closing…

I hope this article and video can be a part of helping vegans and non-vegans better understand one another. You can see the links below and throughout this article for more content on the psychology of eating animals and effective communication between non-vegans and vegans.

I would love to know what you think about everything we covered in the comments! Please share this post to help other humans better understand our shared humanity.

To stay in the loop about new Bite Size Vegan content and updates, please sign up for the newsletter or follow the Telegram channel for the most reliable notifications.

To support educational content like this, please consider making a donation. Now go live vegan, and I’ll see you soon.

— Emily Moran Barwick

Emily, what a profoundly insightful analysis of the complex inner workings that underly the animosity toward vegans. I cannot imagine the amount of time, care, and consideration you put into this. You’ve taken a very polarizing matter and delivered it so thoughtfully and with great compassion and balance.

And you’ve also managed to convey very dense scientific research in a way that will make sense to anyone, yet doesn’t sacrifice the depth of the research with oversimplification! I’m truly blown away… What a monumental resource for all of us. As you’ve said, the more we can understand one another and bring down our defenses, the more we can meaningfully communicate. I’m so grateful for this contribution to the world.

Anesh, I’m truly touched and quite moved by your words. This was indeed an epic undertaking about two months in the making! It’s really a battle to find a way to summarize so much research without oversimplifying the science, but not be so dense that it’s too much for a general audience. And also attend to pacing and attention span of digital content and social media, while also being very mindful of all audiences. I wanted to present this in a way that was as disarming as possible to everyone as none of us can effectively take in information with our defenses up! I really do hope this video and article help foster understanding and communication. Thank you so much again for your kind feedback!

another thoughtful, well researched presentation, so appreciate your work!! I empirically knew this, but nice to have science back it up.

Thank you so much, Cathleen! And yes, as I went through the research, it was interesting to see so many conclusions I’d come to organically through my own experience and thought processes throughout my life and activism. Things I’ve said many times in many videos and speeches now in scientifically backed black and white. So glad you enjoyed it!

Great video, Emily!

Thank you so much, Freya!

Dear Emily,

That was brilliantly done. I just Love your work! You put your heart and soul into everything you do. Your compassion for animals is unmatched. You teach us so much about the importance of treating animals with love and kindness.

Wow thank you, Stephen. That means the world to me. I’m so honored.

Thank You Emily, we all know the hard work you put in to allow the these beautiful animals to enjoy their lives as we do.

Thank you so very much, Stephen. I appreciate that more than I can say!

WOW! This is amazing and densely-packed – deserves a re-watch or two. Again, I feel less isolated knowing someone else “gets” how I feel at a deeper and more nuanced level.

Ad hominem attacks have always baffled me (as they also come from professed animal-lovers who have beloved dogs).

“Anticipated moral reproach” puts a term to the feeling I always have that simply being in a room as a vegan or saying “I don’t eat food with animal products” provokes a powerful reflexive response even from close friends: despite knowing me for many years (as a vegetarian), they have assumed that I am judging them! I’d felt but never understood how being someone who has always loved animals but now expresses this with a deepened understanding and greater care in behaviors should be a challenge to another’s identity (i.e., how does my not doing harm hurt you). Knowing now that the basis of this is actually _shared values_ is is a relief.

Thank you, again Emily!

Thank you so very much. I’m truly honored to hear this. And I’m very, very touched that this helped you feel less isolated. That means more to me than I can possibly tell you.

I’m so, so glad that you gained so much comfort from the concept of anticipated moral reproach as well! You may really enjoy reading through some of the full-length studies. They are very validating in addition to being illuminating. Thank you for taking the time to comment and share this moving feedback!

What is missing with the vegan movement is holding animal agriculture industry to account. They are operating on what is an acceptable animal exploitation business model. Pushing their product with higher and higher yeilds for bigger and bigger profits putting us all at risk of deteriorating health and environmental disaster. We must start connecting the dots. We must educate people on better, healthier, kinder choices if we ever expect more public support.

People will not change their very ingrained eating habits unless we can convince them there is very good reasons to change. I think the vegan movement should teach people to slowly transition and provide the excellent reasons for doing so. It is overwhelming to people to think they should just give up meat products. It is a very big undertaking for families to meal plan without meat and dairy when they have accepted this diet as normal and good for them.

Thank you for your input, Judy. The movement could indeed benefit from a shift from the “individual choice” to a societal transition away from eating animals. And a focus on us as citizens fighting for our planet and community’s health from destructive industries. If you haven’t already you’d probably enjoy reading the key message recommendations from Pax Fauna, which really speak to your own thoughts here. (That’s linked under the “Communication with Non-Vegans (for Vegans)” column at the base of this post under my sign-off). Appreciate you sharing!

Hearts need to change; reason is not sufficient. I try to remain humbled by remembering how we have all been indoctrinated from childhood by toys and adverts to put farmed animals in a different (utilitarian) category.

The good news is that so much can be learned from the Internet: joyful stories from animal sanctuaries that move the heart, activist videos that reveal what industry and ag-gag laws hide from the public, and great recipes!

Absolutely. Change must come from many facets, as the reasons for continuing to eat animals come from many facets (emotional, cultural, social, etc).

I did enjoy this article. It has given me new ideas to think over. I never knew what non-vegans are thinking or going through. I thought it very thought provoking that the way vegans are treated was a deterrent for non-vegans to become vegans. That is what I love about you Emily; you see both sides and educate people to also see both sides and understand each other. This fosters mutual respect of all.

Thank you so much for this, Sally. As always, you make me feel like my efforts and the care I put into my work are seen and appreciated. I did find that particular study fascinating and (as I shared) promising in a way…it can certainly be viewed through a negative interpretation, and does indicate barriers. But I always like to highlight the demonstration of empathy and understanding that the non-vegans organically connected with. Very glad that you found this thought provoking!

I do see lots of ‘justification’ situation. Meat eaters like to eat meat so they need justification, so they would criticize vegan diet being not nutritious, I met quite a few of them. But fact is they don’t care about nutrition, when they order a meal, it has to be tasty, or they will move to other restaurants, they are not ordering the food that are nutritious, they are ordering the food that are delicious.

As a 3+ year Vegan, this video made me cry. Firstly, this video is an absolute treasure trove of amazing analyses and insights into Vegan psychology. I will be referencing this video a lot in my activism. It’s clear you put your heart and soul into this and the flow charts were a much needed addition.

Secondly, this video handed me the bittersweet truth as to why I constantly feel so damn lonely as a Vegan. At first, I felt lonely because I always thought everyone was judging me, but then I realized that I feel lonely because everyone is really just judging themselves and projecting it onto me. Most people don’t want to change and I don’t like to be friends with those people. Even though I try my best to remind myself that the hatred I get is simply a reflection of the omnivorous mind and that I speak on behalf of the animals, I can’t deny that it’s still hatred toward me nonetheless, and it hurts. It’s nice to know that scientific studies prove this and I love how you put a positive twist on it in the end. It’s very easy to make it an us vs them, but reality is so much more nuanced than that and you showcasing that is so sweet. Thank you for this amazing video.

Wow. This comment means more to me than I can possibly tell you. I did truly pour my whole self into this over the last 2 months. And I, too, was brought to tears many times in the process…primarily from just the sheer weight of human anguish, animosity, distress, fear, misunderstanding, and more than anything the fact that so much of the pain comes from pain. So much of why we hurt other people comes from our own wounds. And I found myself wanting us all to be able to hold space for all our wounded parts and find our shared humanity there.

You are not alone in your feelings of isolation and loneliness. Knowing the reasons behind people’s behavior doesn’t necessarily mean that behavior hurts any less. There are very real costs to being vegan. I was worried in this video and article that I was shortchanging that side of it all. But I had to purposefully keep as focused as I could on the premise (why people hate vegans vs getting too deep into the vegan side)…otherwise this would be a 40 hour video! Even with that “narrow” focus, there is so much I didn’t get to!

But I do hope in the future to make a video/article on the “costs” of veganism. Because they are very real. And within several of the studies I read, researchers noted how that is an area that deserves more research and attention. It can be devastating for existing vegans, and stop others from considering veganism. This is why it’s so vital that we as a society become more accepting and open…even if not going vegan, refusing to stigmatize people who are is itself an act that would collectively move forward veganism.

I’m truly honored by your thoughtful consideration and response to this video. And I do feel your pain. I do always make an effort to bring a positive thread into what I convey…even in those studies demonstrating bias and negativity. I want to find those threads…but I feel the weight of it all.

One small consideration; while meat-eaters may self-identify as “carnivores” or “omnivores”, they are not, in fact, anatomically similar to either obligate or facultative carnivores (cats, dogs, etc.) or omnivores (bears, etc.). Their choices have no effect on their anatomy (human anatomy most closely follows frugivore anatomy). The consumption of meat and a meat-based diet has been more accurately termed “carnist” by Melanie Joy, PhD in her book Why We Love Dogs, Eat Pigs, and Wear Cows: An Introduction to Carnism.*

Dr. Joy coined the term “carnism” in 2001 and developed it in her doctoral dissertation in 2003. She considers carnism a subset of speciesism.

Just sayin’

*Joy, Melanie, PhD. 2009. Why We Love Dogs, Eat Pigs, and Wear Cows: An Introduction to Carnism: Red Wheel / Weiser, LLC, 65 Parker St. Suite 7, Newburyport, MA, 10950.

Michael, thank you so much for your comment. In the article section of “A Note on Terminology & Limitations” I explain why I’m using “omnivore” throughout the article (as well as the issues with it as a term). In my very first citation from that section, I link to a number of sources, including Dr. Melanie Joy’s book (which is also cited a few more times) as her work focuses on this lack of defined term for people who consume animal products.

Dr. Joy’s concept of “carnism” is a profoundly useful and monumental contribution to our understanding of the pervasive aspects of animal consumption, and our ability to speak about it effectively. I utilized “omnivore” and “omnivorous” within this article and video not only because those were the primary terms used in the studies I’m covering, but also for familiarity for a general audience.

It’s always a battle to balance the considerations of audience in regards to terminology, especially considering that utilizing verbiage that’s unfamiliar or overly clinical/scientific/foreign can create additional barriers to the general public’s understanding and relation to the content. It was (and always is) an agonizing process to decide how to present dense content and how far to go into all of the interconnected areas, and how to phrase things with various audiences in mind. There is now an additional expandable tooltip in the paragraph on using “omnivore/omnivorous” with direct quotes about “carnist” and “carnism” from Why We Love Dogs, Eat Pigs, and Wear Cows. I hope this helps clarify!

Thank you..eye opening.. we can be angry..but be angry with compassion. I will be even more mindfully of my speaking and my posts

So glad to hear it, Jacqueline. Thank you for taking the time to share your thoughts!

Very thoughtfully reviewed with articles cited and thought-provoking commentary…thank you for exploring this

issue/problem. Since my education is science-based (BS in Biology, MS in Nutrition, PhD in Health Systems and Research Design/Methodology & Statistics) and my professional journey comprised direct health care, implementation of a computer system in health care facilities, and review of same according to federal & state regulations, I have not

directly felt any bias or ill-will from colleagues, friends, or family. But I understand and feel saddened by those who suffer this negative impact.

I transitioned to a plant-based diet (all vegan) about 30 years ago. Although my MS in Nutrition focused on the need to consume animals in order to meet human nutritional needs, I experienced digestive issues with the animal-based diet and slowly consumed greater amounts of all plant-based items, legumes, vegetables/fruits, grains, & plant-based milks. Simultaneously, I reviewed research studies that addressed all the benefits of this dietary pattern and read books authored by physicians and biochemists. My nutrition consultation to clients, friends, and family centers on eating accordingly, but, I discuss this when asked questions and, I believe that my good health “speaks volumes”. I am fortunate to enjoy my quality of life, without any medications, script or OTC. And daily, I try to remember to be grateful for my health and any work I accomplish.

Thank you again for discussing this issue and please continue your work on this topic!

Jane, apologies for my delay in seeing your comment! I so appreciate you taking the time to share this. I’m glad that you’ve not personally experienced anti-vegan bias, and that you are in such great health! It’s true that not everyone who is vegan comes up against bias. But very many do. Again, thank you so much for taking the time to share about your experience and background!