Is silk vegan? Is it cruel? In this video, we look into the ethics of silk, how it’s produced and what alternatives exist.

With all the considerations vegans must make, one that tends to be low on the list is silk. The cruelty of meat, dairy and eggs is painfully evident to anyone who takes a moment to look into their production. Even honey and wool, after some digging (or vegan-nugget-watching), are accepted as inhumane exploitative products. But what about silk? How is it even made and why should vegans be concerned? tweet this

Well to start off, the kind of silk production we’re going to focus on today is that of silkworms, but it should be noted that silk is produced by a number of insects like embioptera, commonly known as web-spinners, hymenoptera (bees, wasps, and ants), silverfish, mayflies, thrips, leafhoppers, beetles, lacewings, fleas, flies, and midges.1 Other types of arthropods also produce silk, most notably various arachnids such as spiders. Spider silk is experimentally being used in the medical field to mend bones and for military purposes to produce an alternative to Kevlar via inserting spider genes into goats so that they excrete silk in their milk, from which protective vests are made.2

The silkworms responsible for the vast majority of commercial silk production, are the bombyx mori domesticated and selectively bred from the wild bombyx mandarina.3 The earliest evidence of silk and silkworm domestication dates back over 5,000 years ago to 3630 BCE in ancient China where sericulture, or silk farming, was born.4 The Chinese emperors tried to keep silk production a secret in order to maintain a monopoly, but by around 200BC sericulture has already crossed into Korea, and later Japan and India.

Note:Some of the statistics in this video post vary widely as various sources seem to disagree as to the actual numbers and/or are unclear in their exact units. I’ve done my best to give you a general impression of the numbers given and document my sources throughout this article.

To understand why silk may be objectionable to vegans, we need to understand how silk is made—and to understand how silk is made, we first need to understand the life cycle of the Bombyx mori.

When a Bombyx mori lays eggs, they typically hatch within 10–14 days. However, depending on the needs of the farmer, they are often placed in refrigeration for months at a time up to a year. Once warmed up again, they generally hatch in the same timeframe. The hatchlings need to be fed immediately as they have a voracious appetite and will die from dehydration and starvation very quickly. The Bombyx mori have a preference for white mulberry leaves (their name is actually latin for “silkworm of the mulberry tree”), and mulberry silk is considered to be the finest and most lustrous.

The hatchlings eat constantly and go through five instars, the term for the developmental stage between molts. Over a period of about 35 days, Bombyx mori shed their skin four times, ending up 10,000 times heavier and 30 times longer than they were upon hatching.5 Once they’ve reached their fifth instar, they enter their pupal stage and encase themselves in cocoons of pure silk.

The silk itself is secreted from two salivary glands in the head of the larvae and consists of two proteins: fibroin, the structural center and sericin—the “gum” which cements the filaments. So yes, those elegant dresses and luxurious sheets…are worm spit. Given the bee regurgitation we like to sweeten our coffee and pastries with, there seems to be a human fascination with utilizing the oral excretions of insects. tweet this

Each cocoon is composed of filaments up to 3,000 feet (914 ) in length, which is pretty impressive coming from a 9 centimeter-long insect.

So at this point, you may be thinking: what’s the harm in harvesting this silk? The little buggers spit it out and sleep in it for a little bit, but it’s not like they’re going to live there forever. Well, this is where the silk production process takes a turn. You see, to get out of their cocoons, silkworms, at this point moths, chew their way out, thus severely shortening the length of the silk threads and decreasing their value and the luster of the material produced.

To avoid this destruction of raw materials, silk farmers will stifle, meaning kill, the pupae by either baking them, immersing them in boiling water, or, less commonly, freezing them or piercing them with a needle. This is performed generally between two days and two weeks after spinning has begun, before they transform into moths.

Once the pupae are dead, cocoons are then soaked in water to be more easily unraveled. The pupae are then discarded or, in some countries, eaten.

If allowed to live past their pupal stage, they would emerge from their cocoons as moths, mate, lay eggs, and die naturally after about a week as they can no longer eat and rely purely upon the nutrients they took in during their larval stage.

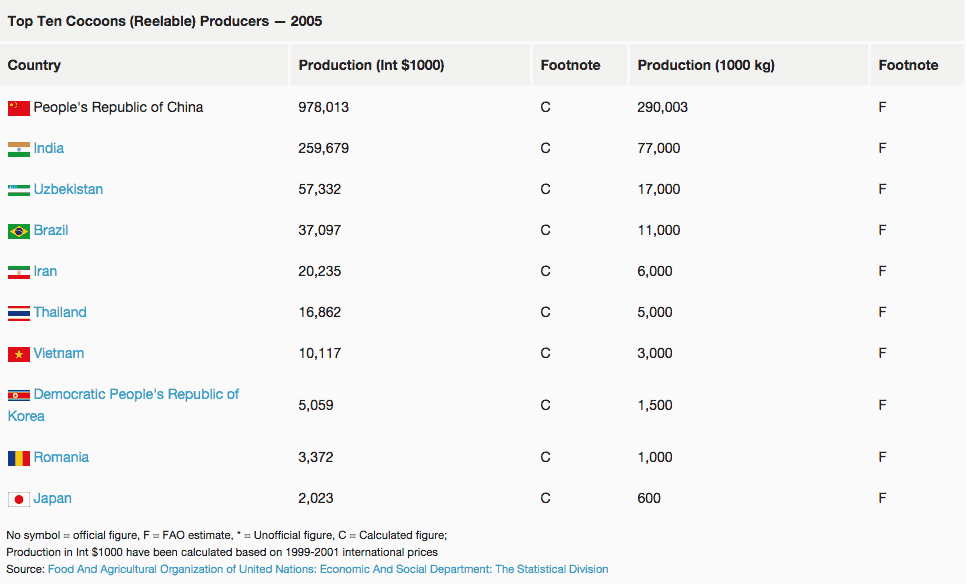

So just how many silkworms are killed every year for the production of silk? This is where I found the greatest variation in statistics. Many articles and websites re-pasted the same statistical table (below)—apparently sourced from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 2005 report (though the table doesn’t match up with their data when searched)6—and stated a blanket number of 70 million pounds for the amount of raw silk produced each year (with no discernible citation).

As of writing this article, the most recent figures available from the FAO state that 161,661 metric tons (356,401,498 pounds) of raw silk was produced worldwide in 2012. This far dwarfs the 70 million pounds I found repeated time and again. The FAO’s larger figure is closely echoed by the International Sericulture Commission, which gives a slightly more conservative estimation of 152,846 metric tons (336,967,749 pounds) for 2012, and provides a 2013 figure of 159,776 metric tons.7 (Note: for the most up-to-date figures for both silk-worm cocoons8 and raw silk production,9 see the respective linked citations).

As far as how many silkworms that means? Those numbers vary as well, but the average range given was 4,400–14,969 per kilogram (2,000–6,804 per pound).10 If applied to the the more conservative 2013 estimate from the International Sericultural Commission of 159,776 metric tons of raw silk produced, anywhere from over 703 billion (703,014,400,000) to over 2 trillion (2,391,686,944,000) worms were killed for silk in 2013. Even using the far more conservative—and, as far as I could tell, completely uncited—figure of 70 worms million pounds, still results in at least 139 billion (139,706,450,400] to over 475 billion (475,287,694,554) worms killed in a given year.

For a fabric that accounts for less than 0.2% of the world fiber market, that’s a pretty staggering death toll.11

Another way silkworms are used is for the production of what’s called silkworm gut, which is mainly used to make fly-fishing leaders. For silkworm gut, silkworms are killed by methods such as submersion in a vinegar solution, just before they are about to spin and their silk glands are removed and stretched into strong threads, which look and feel much like plastic.12

As for whether silkworms or insects in general are sentient and able to experience pain, studies conducted with morphine demonstrate insects’ responses as being indicative of an ability to feel pain, but–the scientific community remains conflicted.13 Silkworms do possess a central nervous system14 and brain15 and definitely display nociception, but an in-depth investigation as to their ability to feel pain will have to be another video entirely. (For an explanation of the difference between nociception and pain, see the post “Do Fish Feel Pain?“)

Even if we assume their death is painless—and we all know what assumptions do—it is still a death, and a human-induced, premature one at that.

An alternative to this method of silk production has arisen called “peace silk” or “Ahimsa silk” after the Sanskrit term for non-violence. There are a number of sources and methods under the “peace silk” umbrella and not all are much different than the traditional approach. The most idealized version of peace silk is that which is harvested in the wild from the empty cocoons of silk moths.

Eri silk, for one, is made from the cocoons of Samia ricini, who leave a little hole in their cocoon from which they emerge. This type of silk cannot be processed like Bombyx mori silk and accounts for a very small portion of the silk market. Ahimsa silk is made from Bombyx mori who have been allowed to go through their metamorphosis, and emerge from their cocoons before the cocoons are harvested. Peace silks are more expensive and less lustrous than traditionally farmed silk, due to the torn cocoons, and make up a small fraction of the overall silk industry.

The clarity of various peace silk suppliers’ actual practices can be difficult to ascertain. Silk moth cultivator Michael Cook wrote an article criticizing the various peace silk methods, pointing to the potential deaths inherent in the next generation of eggs and hatchlings, and the unrealistic idealized notion of wild-picked vacated cocoons.16 Mr. Cook himself raises and kills silk worms, so his input on the possible ethical conflicts of peace silk is interesting to say the least. Peace silk producers have and will refute such criticisms,17 but I think it’s important to fully and deeply investigate any so-called “humane” methods of animal product and byproduct production, and to ask the question of whether the use of living beings in any form can be ethical.

Regardless of their treatment, the fact remains that domesticated silk worms are exploited for their silk. They have been selectively bred with the sole purpose of producing as much silk as possible, much like the animals of the food industry who have been bred into disfigured absurdities to large to support their own bodyweight. The adult Bombyx mori cannot even fly. They also cannot eat due to their reduced mouthpart and small heads—a fact which is often cited as evidence of human manipulation, but this is actually true of all saturniidae (giant silk moths).18

Still, these beings are bred, enslaved, and slaughtered for an unnecessary luxury fabric.

Just because these tiny creatures look so foreign and unlike us doesn’t mean they deserve exploitation. tweet this Their lives may seem brief and inconsequential, but the same could be said for us from an outside perspective. The fact remains they are living beings all their own, with brains and nerves and desires. Now, I can’t presume to know the desires of a silkworm, but I think it’s safe to say that none of them are becoming your dress or bedsheets.

Luckily, there are numerous alternatives to silk including rayon, nylon, milkweed seed pod fibers, silk-cotton tree and ceiba tree filaments, polyester, tencel, and lyocell (a type of cellulose fiber). So you can stay silky without the cruelty.

Now I’d love to hear your thoughts on this–were you aware of the way silk is made? Do you find it problematic? Do you think the “peace silk” methods are acceptable or is the use of being in any form exploitative? Let me know in the comments!

— Emily Moran Barwick

Spider-goats? Something just ain’t right with this. The world done went nuts truly nuts.

i know…i know

Wow! Thank you for explaining this, I knew to avoid silk but I didn’t know the exact process. Spider genes in goats, can the human race ever stop inventing cruel processes.

you’re so welcome! so glad it was helpful :)

I love how thorough you are!

Hi Emily, I love your work and your thoroughness. I am vegan. I do however struggle with the alternatives also. Rayon, nylon, polyester etc even bamboo fabrics. The resources, chemicals used to produce these alternative fabrics, the everlasting pollution and waste left in the environment from production, and products which will not break down in nature. These are so destructive to the environment and to the millions of animals whose habitats are destroyed or are directly killed by poisoning from the chemicals. Even cotton is one of the highest pesticide using products in the world. What is the answer, I do not know. I try and buy all my clothes from op shops now but…… I am at a loss.

this is very true. i purchase everything secondhand myself. There are already enough clothes out there.. Once in a while I might get something new. Usually organic cotton or something of the like… Nothing is perfect however

Hi Emily – thoroughly researched as usual! Yeah, I’ve know about this method since I was a kid (probably at least 50 years ago!), definitely as non-vegan as honey without a shadow of a doubt. Of course, most people would consider the exploitation & killing of moths as insignificant, but if you love all animals and have an unconditional respect for ALL life – then you gotta say no to silk!

BTW – how do you feel about the consumption of palm oil (in so many products now) and it’s cruel and devastating impact on animal life, not least, orangutans? For that reason it has also to be considered non-vegan – do you agree?

nylon manufacture creates nitrous oxide, a greenhouse gas 310 times more potent than carbon dioxide. plus, it’s not bio-degradable.

Can anyone recommend an alternative for a silk pillowcase? My hair is thick and curly and gets all knarly from sleeping. I could probably go more days without washing it, but I don’t want to have a huge rats nest to untangle in the shower. Thanks very much!

I do well with either bamboo or satin (not satin silk, satin that’s made from polyester/mercerised cotton). My hair has actually done better with the satin pillow cases just from the low-end department stores! However, I can’t find an alternative for keratin or hydrolyzed silk for detangling, so hopefully the satin works for you so you don’t need those.

It was not kept secret to protect a monopoly. Why does everyone think money when it comes to secrets?

The process of obtaining the silk was consider an intimate and private process. The product was for use only by the handler and her family. It was kept secret because it was an intimate an dprivate process.

Emily, thank you! Your video is definitely an eye opener! I ascribe to vegan eating, although, I am human; I do love silk. For the last couple of days I have been unpleasantly surprised and annoyed that silkworms have to die for our pleasure. I just find it hard to say no.

So glad to hear this was helpful, Mallory! I hope that the reality of the process continues to work into your conscience…sometimes it takes us a little bit to adjust our actions after learning new information. Many thanks for watching and commenting and much love!

I agree with Kerry and dana, above, that polyester, rayon and other mined and/or extruded fibers are not good options. Setting aside the extraordinary pollution caused in their manufacture, the microplastics released by polyesters every time you wash them end up in our waterways and oceans. They don’t biodegrade but do are ingested by aquatic animals and produce toxins that accumulate up the food chain. My hope is that orange fiber silk and other plant silks will eventually replace them. For now, the issue only affects me when trying to find a biodegradable dental floss. I use an Ahimsa silk dental floss because the vegan flosses all take the form of polymers, which are plastics. Claims of biodegradability have been made but what I’m reading is that these claims are dubious. Even if you make nylon out of bamboo, it’s still nylon.

I looked at Michael Cook’s argument, which seems to be that if you let all your female moths lay eggs it will result in excess larvae that end up dying because you won’t have enough to feed them. That’s true in nature as well. And given that Ahimsa silk is his competitor and he’s trying to justify killing his pupae, I am unpersuaded.

I look forward to the day when there are lovely and possibly fragrant plant-based non-plastic silks. But until that day arrives I’m going to look out for the rivers, streams and oceans by using products that can be composted or indeed used directly as mulch, rather than synthetics.